Iran in 1967 seemed both chaotic and hairy in terms of traffic. Unlike India, drivers seemed intent on forceful progress regardless of fellow road users, neither using a mirror or signalling and constantly attempting to push through tiny gaps. The accident rate then was dreadful and is still one of the three highest in the world. Even using official figures, probably optimistic, road deaths are 32.1 per hundred thousand people compared with 2.9 per hundred thousand in the UK. I don’t think they took a crash too seriously – a collision was referred to as the vehicles “kissing”.

New cars were very quickly bumped and battered but then repaired to keep them on the road indefinitely, bodywork rippled and distorted, engines rough and tyres bald. But fuel was cheap (even today diesel is 6p a litre and petrol 23p) and Iran took to the car very quickly.

There were a variety of cars on the road in the capital, Tehran, but the favourite was the basic Mercedes saloon, widely used as a taxi. Imported German cars were heavily taxed so they were often driven in from Germany through Turkey. This was a tough journey of some 2,700 miles but still thought of as worthwhile. In 1967 Iran did have a home produced car in the form of the Peykan (Arrow in English). This was a complete knockdown Hillman Hunter, later largely made in Iran with variant bodies including a pickup. The Peykan was also used as a taxi and was popular but taxi drivers told me it had a “weak body”; and it is true that it suffered more than the Mercedes in the rough and tumble of Tehran traffic. None the less, the essentially simple and robust Peykan was a sensible choice for Iran.

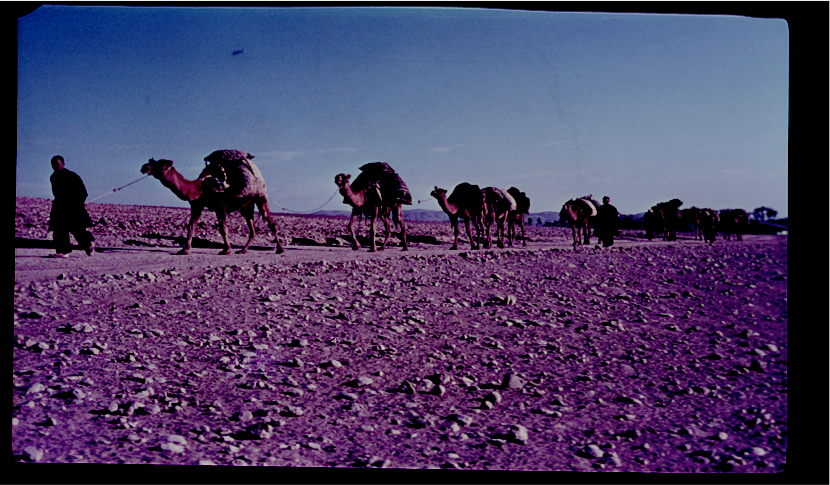

However, I actually worked in a development project in a remote area up in the mountains, between 6,000 and 10,000 feet up. It could be bitterly cold and I remember a local being told off for not fully recording the winter temperatures; he protested that the thermometer was inadequate, only going down to minus 20 oC. There were no surfaced roads, rain could turn low points into a quagmire, snowfall could block roads for many weeks and in summer they became like a washboard. There were no garages, no mechanics; no spares; no phones and no AA rescue service. A demanding environment for a vehicle and you were on your own if it broke down. It had to be reliable; simple to fix, and good for rough conditions. The traditional “vehicles” met those criteria, as you can imagine.

It is probably fair to say no wheeled vehicle met that spec in full but the village bus may have been the closest – simple, robust, good ground clearance and 20 or 30 passengers to push it out when it got stuck! But our Project had three types of vehicles in use; Citroen 2CVs, a long and short wheelbase Land Rover and sometimes a diesel Toyota Land Cruiser. A Citroen 2CV – really? Don’t forget the origin of the little Citroen – for farmers and rough conditions. Good ground clearance and light weight sometimes meant it “floated” over mud where the Land Rover bogged down and it was certainly more comfortable than the pretty bumpy Land Rovers. It was simple but wasn’t that reliable. It struggled a bit on steep sections of mountain roads when it really did seem to be only 2 horsepower but I still think of it with some affection.

And what of the other two? A Toyota was a rare beast in those days and cars from Japan not well regarded by Brits. The Land Rover was tried and tested and sold all over the world – and British had to be best, didn’t it? I’d been used to short wheel base (SWB) Land Rovers in the UK, used on farms, short trips to market, and for putting a couple of sheep in the back. Servicing a project 80 miles from town on slowish roads brought the realisation that a SWB really didn’t have much room. The LWB was much better in that respect and would carry several passengers plus supplies so cutting the number of trips needed. It was a poor ride for passengers and a bit more liable to get stuck in some situations but still the best bet all round.

And the Toyota? This was pretty much on a par with the SWB Land Rover. Only three forward gears in each ratio but this didn’t matter because of the better engine. It seemed heavier which could be a disadvantage in mud but it was still a very capable vehicle. It was a bit more comfortable but, despite being mechanically more complex, its main advantage over the Land Rovers was that it was more reliable.

It was prone to rust at that stage of production but this hardly mattered in the Iranian desert – very dry for most of the year and with unsalted roads. By the time I left Iran in 1969, there seemed to be more of them about but I saw few Land Rovers. Looked at now, they have both been remarkably successful vehicles and highly regarded; and even the little 2CV has become an icon.

Leave a Reply